Learning to be Hedonists in Paradise

In the name of God, the Most Merciful, the Most Compassionate

In the course of his Tanner lectures, Death and the Afterlife (pp. 96-100), Samuel Scheffler argues that valuing something in a recognisably human way requires being temporally bounded (i.e. not living forever). This is because to value x involves making decisions to prioritise x in the background of scarcity, i.e. where we choose x over y, for instance, and where we fear the loss of x. For instance, I value reading novels, and so I make active choices to choose novel-reading over cooking, knowing that I only have a limited time to do so. The prospect of being unable to read makes me anxious and I fear the loss of being able to read (e.g. if I lose my books in a fire).

Decision-making under scarcity is not possibly in an everlasting life. Whatever such an eternity might be, it is not a recognisably human way of valuing something. And so, a biological, mortal existence is necessary to valuing something:

The point is not merely that without death we would not have what we are accustomed to thinking of as lives, although that is certainly true; the more important point is that our confidence in the values that make our lives worth living depends on the place of the things that we value in the lives of temporally bounded creatures like ourselves. Rather than giving us an eternity to relish these things, immortality would undermine the conditions of our valuing them in the first place. (Scheffler 2013, p. 100 of Death and the Afterlife)

Let us grant this view of valuing. Naturally, this raises two questions for a Muslim: (1) can God value things (where “to value” means “to value in a way we can recognise/understand as humans”)? and (2) if we go to Heaven, which is everlasting, can we value things? I want to think more closely about the second question.

The various Qur’anic verses and ahadith (sayings of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ) regarding Heaven seem, to me, to fall into at least three categories:

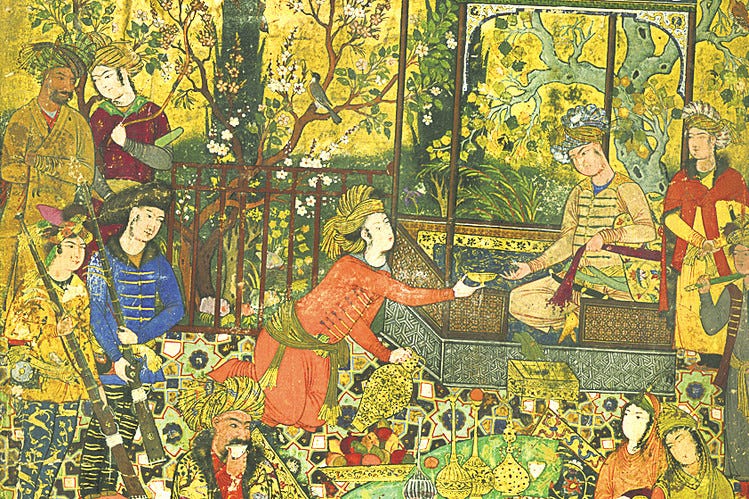

a) sensory pleasure e.g. “In it are rivers of water unaltered, rivers of milk whose taste never changes, rivers of wine delightful to those who drink, and rivers of purified honey.” (Qur’an 47:15)

b) companionship and conversation e.g.“They will not hear therein ill speech or commission of sin—only a saying: ‘Peace, peace.’” (Qur’an 56:25–26)

c) vision or knowledge of God e.g. “Faces that Day will be radiant, looking at their Lord.” (Qur’an 75:22–23)

d) absence of fear of loss, anguish, grief etc. e.g. “No fear will there be concerning them, nor will they grieve.” (Qur’an 2:62)

(Perhaps there are more categories; I am not an Islamic scholar by any means.)

There are two points to note here. First, Heaven fulfills Scheffler’s conditions for a life without (a distinctly human) value. In other words, there is no sense of scarcity, fear, etc. and it is everlasting. There are, of note, multiple levels of Heaven (e.g. Qur’an 55:62) - and in fact, a-c probably coincide to some of these levels (although I was not able to find a source of this, but c is certainly considered the highest level). But for whatever reason, the lower levels do not feel resentment or envy at not having achieved the levels above them (e.g. “and We shall remove any bitterness from their hearts: [they will be like] brothers, sitting on couches, face to face” (Quran 15:47)), even though they are aware of these higher levels like distant stars in the horizon to their eyes.

Second, a-c can all be described as various types of bliss or pleasure, and d tells us that there is nothing besides this: it is perfectly pleasurable. Even the vision of God is ultimately the experience of pleasure. The good life is, basically, hedonistic.

So, if we take Scheffler’s point seriously, Heaven does not contain anything like a recognisably human version of valuing things. This is rather disappointing and perhaps even frightening: why should we aim for something so oddly inhuman, almost a caricature of a life that we would admire or aspire towards? Isn’t there an unbreachable gap between my ambitions in this life—where I am trying to preserve, sustain, and work towards what I value—and my ambitions in the afterlife, where I am suddenly adrift and incapable of valuing things at all? It would seem that the very activity of valuing, around which our human lives revolve, would be pointless.

I think we should take it to be the case that experiencing pleasure or hedonism a la Paradise is more complicated than it may seem. This life is essentially a training ground in which we learn to experience pleasure, and valuing things in this life is how we cultivate this ability of Paradisal hedonism.

This isn’t an entirely new idea. Consider the idea amongst hedonists that the best pleasures are intellectual and that this is something a person has to learn to recognise by suppressing sensory pleasures. The idea that we have to train ourselves to experience pleasure properly is one way of making hedonism more appealing and less carnal than it initially would seem.

What I want to do is slightly different. I am not trying to claim pleasure is more complicated than one would think or that there are levels to pleasure. I take it for granted that if Prophet Muhammad ﷺ has said that Paradise has delicious grapes, then there are truly delicious grapes there — not some sort of intellectual grapes. Rather, what I want to say is that the ability to experience even the simplest pleasures properly, without the spectre of anxiety and regret, is a religious ability, and that Islam encourages the cultivation of this ability in order to become real hedonists. The familiar criticism of Islamic Paradise — that it is filled with carnal pleasures — is right (or at least, I won’t claim to be knowledgeable enough to dispute what the text plainly says). But the idea that being a Muslim hedonist is easy is wrong. So, my aim is to link Islamic Paradisal hedonism to: (1) valuing things in this life and (2) fundamental Islamic practices such as prayer, fasting, alms-giving, and pilgrimage.

Consider this: Aisha decides to pray the Zuhr, or noon, prayer. She knows she only has a set amount of time to pray Zuhr before the next afternoon prayer timing arrives. She decides to pray Zuhr, even though she wants to finish a very funny episode of The Office (US version, of course). Even though she hates turning off her TV, she fears missing prayer-time more. Even when she is lazy, she tells herself to fear missing prayer-time. And when she raises children, she will try to preserve the value of prayer by teaching them of it. In short: Aisha values praying.

Essentially, all Islamic practices involve attenuating a person to the process of valuing. This is because they all require a person make a decision in a restricted amount of time. Charity/alms-giving (zakat) has to be donated annually. Fasting has to be done daily for a month. The five prayers have strict timings within which they must be prayed daily. The last pillar of Islam, Hajj or the pilgrimage to Makkah, must be done once in a lifetime. All of these practices teach us how to value by forcing us to value them, at risk of Hell or at least punishment. Even their repentance, while unrestricted in that a person can repent at any point in time, has conditions; I have to make up a missed prayer as soon as I remember that I missed it, for example.

In other words, Islamic practices not only require that we value them, but teach us how to value by foregrounding temporal scarcity in our decisions. We cannot forget that we must value things, that valuing requires choosing the valued over other desirable but less valued objects. We become habituated to valuing, whether we like it or not. We become the sorts of beings who value. (Note also that the high stakes of Heaven and Hell force us to deal with this, to learn to actively value, because of how stark and dark the consequences of a life of forgetfulness are. Indeed, the primary Islamic accusation against man is not that of being evil, but of being forgetful, avoidant (Quran 87:19).)

So much for explicitly religious practices, such as prayer. But as every Muslim knows, any permissible action can be a form of worship so long as it is done with an intention to please God. Thus, our realm of valuing expands — trained as we are in valuing through religious practice — to include even such trivialities as reading a novel or driving a car.

This practice of learning to value is the paradigmatic Islamic virtue: being patient. Patience (sabr) is the religious gloss of value: it is making a decision to prioritise x over y, specifically when it is difficult to do so. The story of Prophet Job (peace be upon him) is the quintessential example of sabr. But really, all practices involve sabr: Aisha knows that she gave up The Office for a reward for which she must be patient.

So much for Islamic practices. But how is this linked to pleasure? For we often value things without finding them pleasurable, and many things are pleasurable without being valuable.

The valuing in this life is a formative condition for the pleasure in the next one. Because we value things — and give up others — in this life, we become the sorts of beings who can experience pleasure.

One way this might be thought to be the case is the Avicennan (Ibn Sina) solution: heaven is a psychological state of the soul which has learned to become detached from the body through philosophical-religious practices. Because it has learned to do so, when it is disembodied in the afterlife, it does not seek bodily pleasures (which it cannot attain), but rejoices in intellectual pleasures. This is what differentiates a heavenly soul from a hellish one: the hellish one longs for what it can no longer have (see Ibn Sina and Mysticism by Shams Inati, p. 77-79, a translation of part 4 of his Al-Isharat wa al-Tanbihat).

The Avicennan solution requires that we train ourselves for a particular type of pleasure, i.e. a disembodied, intellectual sort, in accordance with his belief in substance dualism. But I want to suggest a view where training oneself for pleasure is linked to the temporal limitations that are essential in the practice of valuing, rather than to embodied ones.

Quintessentially, temporal limitations force us to prioritise and to give up things. This prioritisation is what makes us anxious over loss. Sabr means that we must learn to find trust despite the apparent loss. The view is that when we value x for the sake of God — where x can be distinctly religious like prayer or implicitly religious like a well-intentioned “secular” act — we must trust that God has planned what is best for us and have patience in awaiting the fruits of our labour.

The biggest barrier to pleasure, then, is psychological: our willingness to accept uncertainty and our tendency for FOMO. Who hasn’t eaten a chocolate cake at Chili’s while eyeing the peace pie at someone else’s table? Who hasn’t given up the pleasure of sleeping in to go to the gym, while worrying that the dividends of exercise won’t be paid? By putting us in a world where we have to prioritise, i.e. value, things, God has forced us to confront this uncertainty and potential for regret and loss. As we train ourselves to continue to be patient in the face of apparent loss, we become the sorts of beings who can experience category d, i.e. freedom from anxiety and fear. And once we are eventually given infinite goods in a non-zero-sum world, we are ready to approach them with this restful, patient attitude: being able to experience true unadulterated pleasure is a state of blessedness, the Paradisal state.

In other words, valuing — which is unavoidable in our human life — without sabr inevitably leads to fear, if not regret and grief. Even placed within an infinite life with infinite goods, such a person would experience anxiety. Valuing with sabr is a process of learning to live with our fears and griefs reposed in God, thus creating room for pleasure, for being hedonists.

(This raises the important question of why we do not experience Paradise here through our own conceptions of sabr: why does the Qur’an speak of the afterlife as the place where God removes fear and grief? For instance, Qur’an 7:43: “And We will remove whatever is in their breasts of resentment, and beneath them rivers will flow. And they will say: ‘Praise be to Allah who has guided us to this.” I think this is because, ultimately, this life does involve loss. There is another step required, other than my cultivation of hedonism: that step is that God actually removes the sources of grief, loss, and anxiety. We do not even have to be patient in the afterlife. Like everything else in Islam, the ultimate power of the culmination of sabr is God’s.)

Seen from this lens, a Muslim’s life is a process of learning to experience pleasure, of cultivating a Paradisal hedonism. Ironically, it is only by exposing oneself to loss that one can ready oneself for bliss. Scheffler is right that the afterlife, in its infinitude, is not a distinctly human life which revolves around valuing goods. Rather, valuing is the way in which we shed the constraints which prevent us from experience the pleasure which God intends for us, the pleasure which He has made obligatory upon us, the pleasure of being blessed. Paradise is post-human: it becomes possible only when the quintessentially human work of valuing has taught us to be hedonists.

“He has obligated you to serve Him but in doing so He has only obligated you to enter His Paradise.” (Ibn Ataillah, Al-Hikām, tr. Danner)

And God knows best.

- MM, January 18th, 2025

Comments

Post a Comment

please share your thoughts below